Functional divisions

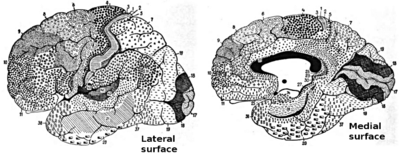

CytoarchitectureResearchers who study the functions of the cortex divide it into three functional categories of regions. One consists of theprimary sensory areas, which receive signals from the sensory nerves and tracts by way of relay nuclei in the thalamus. Primary sensory areas include the visual area of the occipital lobe, the auditory area in parts of the temporal lobe andinsular cortex, and the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. A second category is the primary motor cortex, which sends axons down to motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord. This area occupies the rear portion of the frontal lobe, directly in front of the somatosensory area. The third category consists of the remaining parts of the cortex, which are called the association areas. These areas receive input from the sensory areas and lower parts of the brain and are involved in the complex processes of perception, thought, and decision-making.

Different parts of the cerebral cortex are involved in different cognitive and behavioral functions. The differences show up in a number of ways: the effects of localized brain damage, regional activity patterns exposed when the brain is examined using functional imaging techniques, connectivity with subcortical areas, and regional differences in the cellular architecture of the cortex. Neuroscientists describe most of the cortex—the part they call the neocortex—as having six layers, but not all layers are apparent in all areas, and even when a layer is present, its thickness and cellular organization may vary. Scientists have constructed maps of cortical areason the basis of variations in the appearance of the layers as seen with a microscope. One of the most widely used schemes came from Korbinian Brodmann, who split the cortex into 51 different areas and assigned each a number (many of theseBrodmann areas have since been subdivided). For example, Brodmann area 1 is the primary somatosensory cortex, Brodmann area 17 is the primary visual cortex, and Brodmann area 25 is the anterior cingulate cortex.

Topography

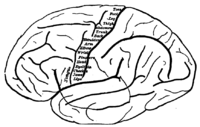

Many of the brain areas Brodmann defined have their own complex internal structures. In a number of cases, brain areas are organized into "topographic maps", where adjoining bits of the cortex correspond to adjoining parts of the body, or of some more abstract entity. A simple example of this type of correspondence is the primary motor cortex, a strip of tissue running along the anterior edge of the central sulcus, shown in the image to the right. Motor areas innervating each part of the body arise from a distinct zone, with neighboring body parts represented by neighboring zones. Electrical stimulation of the cortex at any point causes a muscle-contraction in the represented body part. This "somatotopic" representation is not evenly distributed, however. The head, for example, is represented by a region about three times as large as the zone for the entire back and trunk. The size of any zone correlates to the precision of motor control and sensory discrimination possible. The areas for the lips, fingers, and tongue are particularly large, considering the proportional size of their represented body parts.

In visual areas, the maps are retinotopic—that is, they reflect the topography of the retina, the layer of light-activated neurons lining the back of the eye. In this case too the representation is uneven: the fovea—the area at the center of the visual field—is greatly overrepresented compared to the periphery. The visual circuitry in the human cerebral cortex contains several dozen distinct retinotopic maps, each devoted to analyzing the visual input stream in a particular way. The primary visual cortex (Brodmann area 17), which is the main recipient of direct input from the visual part of the thalamus, contains many neurons that are most easily activated by edges with a particular orientation moving across a particular point in the visual field. Visual areas farther downstream extract features such as color, motion, and shape.

In auditory areas, the primary map is tonotopic. Sounds are parsed according to frequency (i.e., high pitch vs. low pitch) by subcortical auditory areas, and this parsing is reflected by the primary auditory zone of the cortex. As with the visual system, there are a number of tonotopic cortical maps, each devoted to analyzing sound in a particular way.

Within a topographic map there can sometimes be finer levels of spatial structure. In the primary visual cortex, for example, where the main organization is retinotopic and the main responses are to moving edges, cells that respond to different edge-orientations are spatially segregated from one another.

Development

Main article: Neural development in humans

Further information: Human brain development timeline

During the first three weeks of gestation, the human embryo's ectoderm forms a thickened strip called the neural plate. Theneural plate then folds and closes to form the neural tube. This tube flexes as it grows, forming the crescent-shaped cerebral hemispheres at the head, and the cerebellum and pons towards the tail.

Function

Cognition

Main articles: Cognition and Mind

Understanding the mind–body problem – the relationship between the brain and the mind – is a significant challenge both philosophically and scientifically. It is very difficult to imagine how mental activities such as thoughts and emotions could be implemented by physical structures such as neurons and synapses, or by any other type of physical mechanism. This difficulty was expressed by Gottfried Leibniz in an analogy known as Leibniz's Mill:

Doubt about the possibility of a mechanistic explanation of thought drove René Descartes, and most of humankind along with him, to dualism: the belief that the mind exists independently of the brain. There has always, however, been a strong argument in the opposite direction. There is clear empirical evidence that physical manipulations of, or injuries to, the brain (for example by drugs or by lesions, respectively) can affect the mind in potent and intimate ways. For example, a person suffering from Alzheimer's disease – a condition that causes physical damage to the brain – also experiences a compromised mind. Similarly, someone who has taken a psychedelic drug may temporarily lose their sense of personal identity (ego death) or experience profound changes to their perception and thought processes. Likewise, a patient withepilepsy who undergoes cortical stimulation mapping with electrical brain stimulation would also, upon stimulation of his or her brain, experience various complex feelings, hallucinations, memory flashbacks, and other complex cognitive, emotional, or behavioral phenomena. Following this line of thinking, a large body of empirical evidence for a close relationship between brain activity and mental activity has led most neuroscientists and contemporary philosophers to be materialists, believing that mental phenomena are ultimately the result of, or reducible to, physical phenomena.

Lateralization

Main article: Lateralization of brain function

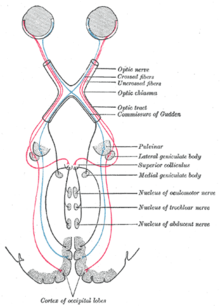

Each hemisphere of the brain interacts primarily with one half of the body, but for reasons that are unclear, the connections are crossed: the left side of the brain interacts with the right side of the body, and vice versa. Motor connections from the brain to the spinal cord, and sensory connections from the spinal cord to the brain, both cross the midline at the level of the brainstem. Visual input follows a more complex rule: the optic nerves from the two eyes come together at a point called the optic chiasm, and half of the fibers from each nerve split off to join the other. The result is that connections from the left half of the retina, in both eyes, go to the left side of the brain, whereas connections from the right half of the retina go to the right side of the brain. Because each half of the retina receives light coming from the opposite half of the visual field, the functional consequence is that visual input from the left side of the world goes to the right side of the brain, and vice versa. Thus, the right side of the brain receives somatosensory input from the left side of the body, and visual input from the left side of the visual field—an arrangement that presumably is helpful for visuomotor coordination.

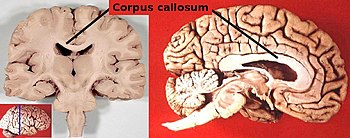

The two cerebral hemispheres are connected by a very large nerve bundle (the largest white matter structure in the brain) called the corpus callosum, which crosses the midline above the level of the thalamus. There are also two much smaller connections, theanterior commissure and hippocampal commissure, as well as many subcortical connections that cross the midline. The corpus callosum is the main avenue of communication between the two hemispheres, though. It connects each point on the cortex to the mirror-image point in the opposite hemisphere, and also connects to functionally related points in different cortical areas.

In most respects, the left and right sides of the brain are symmetrical in terms of function. For example, the counterpart of the left-hemisphere motor area controlling the right hand is the right-hemisphere area controlling the left hand. There are, however, several very important exceptions, involving language and spatial cognition. In most people, the left hemisphere is "dominant" for language: a stroke that damages a key language area in the left hemisphere can leave the victim unable to speak or understand, whereas equivalent damage to the right hemisphere would cause only minor impairment to language skills.

A substantial part of current understanding of the interactions between the two hemispheres has come from the study of "split-brain patients"—people who underwent surgical transection of the corpus callosum in an attempt to reduce the severity of epileptic seizures. These patients do not show unusual behavior that is immediately obvious, but in some cases can behave almost like two different people in the same body, with the right hand taking an action and then the left hand undoing it. Most of these patients, when briefly shown a picture on the right side of the point of visual fixation, are able to describe it verbally, but when the picture is shown on the left, are unable to describe it, but may be able to give an indication with the left hand of the nature of the object shown.

Language

Main article: Language processing in the brain

Since then, there has been substantial debate over what linguistic processes these and other parts of the brain subserve, and although Broca's and Wernicke's areas have traditionally been associated with language functions, they may also be involved in certain non-speech functions. There is also debate over whether or not there even is a strong one-to-one relationship between brain regions and language functions that emerges during neocortical development. More recently, research on language has increasingly used more modern methods including electrophysiology and functional neuroimaging, to examine how language processing occurs. In the study of natural language, a dedicated network of language development has been identified as crucially involving Broca's area.

Metabolism

The brain consumes up to twenty percent of the energy used by the human body, more than any other organ.Brain metabolism normally relies upon blood glucose as an energy source, but during times of low glucose (such as fasting, exercise, or limited carbohydrate intake), the brain will use ketone bodies for fuel with a smaller need for glucose. The brain can also utilize lactate during exercise. Long-chain fatty acids cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, but the liver can break these down to produce ketones. However the medium-chain fatty acidsoctanoic and heptanoic acids can cross the barrier and be used by the brain. The brain stores glucose in the form of glycogen, albeit in significantly smaller amounts than that found in the liver or skeletal muscle.

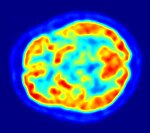

Although the human brain represents only 2% of the body weight, it receives 15% of the cardiac output, 20% of total body oxygen consumption, and 25% of total body glucoseutilization. The need to limit body weight has led to selection for a reduction of brain size in some species, such as bats, who need to be able to fly. The brain mostly uses glucose for energy, and deprivation of glucose, as can happen in hypoglycemia, can result in loss of consciousness. The energy consumption of the brain does not vary greatly over time, but active regions of the cortex consume somewhat more energy than inactive regions: this fact forms the basis for the functional brain imaging methods PET and fMRI. These are nuclear medicine imaging techniques which produce a three-dimensional image of metabolic activity.

Clinical significance

Clinically, death is defined as an absence of brain activity as measured by EEG. Injuries to the brain tend to affect large areas of the organ, sometimes causing major deficits in intelligence, memory, personality, and movement. Head trauma caused, for example, by vehicular or industrial accidents, is a leading cause of death in youth and middle age. In many cases, more damage is caused by resultant edema than by the impact itself. Stroke, caused by the blockage or rupturing of blood vessels in the brain, is another major cause of death from brain damage.

Other problems in the brain can be more accurately classified as diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases, such asAlzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and motor neuron diseases are caused by the gradual death of individual neurons, leading to diminution in movement control, memory, and cognition. There are five motor neuron diseases, the most common of which is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Some infectious diseases affecting the brain are caused by viruses and bacteria. Infection of the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain, can lead to meningitis. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (also known as "mad cow disease") is deadly in cattle and humans and is linked to prions. Kuru is a similar prion-borne degenerative brain disease affecting humans, (endemic only to Papua New Guinea tribes). Both are linked to the ingestion of neural tissue, and may explain the tendency in human and some non-human species to avoid cannibalism. Viral or bacterial causes have been reported inmultiple sclerosis, and are established causes of encephalopathy, and encephalomyelitis.

Brain tumors both benign and malignant can form. These can either originate in the cerebral tissue or in the meninges. The most common are those growths that affect the glial cells known as gliomas. (This term has been extended to include all primary brain tumors.)] Secondary cancers can form in the brain as a result of brain metastasis.

Mental disorders, such as clinical depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder may involve particular patterns of neuropsychological functioning related to various aspects of mental and somatic function. These disorders may be treated by psychotherapy, psychiatric medication, social intervention and personal recovery work or cognitive behavioural therapy; the underlying issues and associated prognoses vary significantly between individuals.

Many brain disorders are congenital, occurring during development. Tay-Sachs disease, fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome are all linked to genetic and chromosomal errors. Many other syndromes, such as the intrinsic circadian rhythmdisorders, are suspected to be congenital as well. Normal development of the brain can be altered by genetic factors, drug use, nutritional deficiencies, and infectious diseases during pregnancy.

Epileptic, and non-epileptic seizures can cause cognitive impairment when the seizures become widespread, occur repeatedly in the same brain area or last for too long. Seizures can be assessed using EEG and various medical imagingtechniques. They can sometimes be treated using anticonvulsant drugs and certain neurosurgical procedures and auxiliary treatments may also be used.

Effects of brain damage

A key source of information about the function of brain regions is the effects of damage to them. In humans, strokes have long provided a "natural laboratory" for studying the effects of brain damage. Most strokes result from a blood clot lodging in the brain and blocking the local blood supply, causing damage or destruction of nearby brain tissue: the range of possible blockages is very wide, leading to a great diversity of stroke symptoms. Analysis of strokes is limited by the fact that damage often crosses into multiple regions of the brain, not along clear-cut borders, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are mini-strokes that can cause sudden dimming or loss of vision (including amaurosis fugax), speech impairment ranging from slurring to dysarthria or aphasia, and mental confusion. But unlike a stroke, the symptoms of a TIA can resolve within a few minutes or 24 hours. Brain injury may still occur in a TIA lasting only a few minutes.A silent stroke or silent cerebral infarct (SCI) differs from a TIA in that there are no immediately observable symptoms. An SCI may still cause long lasting neurological dysfunction affecting such areas as mood, personality, and cognition. An SCI often occurs before or after a TIA or major stroke.

Electrodes and magnetic fields

By placing electrodes on the scalp, it is possible to record the summed electrical activity of the cortex using a methodology known as electroencephalography (EEG). EEG records average neuronal activity from the cerebral cortex and can detect changes in activity over large areas but with low sensitivity for sub-cortical activity. EEG recordings are sensitive enough to detect tiny electrical impulses lasting only a few milliseconds. Most EEG devices have good temporal resolution, but low spatial resolution.

Electrodes can also be placed directly on the surface of the brain (usually during surgical procedures that require removal of part of the skull). This technique, called electrocorticography (ECoG), offers finer spatial resolution than electroencephalography, but is very invasive. In addition to measuring the electric field directly via electrodes placed over the skull, it is possible to measure the magnetic field that the brain generates using a method known asmagnetoencephalography (MEG). This technique also has good temporal resolution like EEG but with much better spatial resolution. The greatest disadvantage of MEG is that, because the magnetic fields generated by neural activity are very subtle, the neural activity must be relatively close to the surface of the brain to detect its magnetic field. MEGs can only detect the magnetic signatures of neurons located in the depths of cortical folds (sulci) that have dendrites oriented in a way that produces a field.

Imaging

Further information: Brain mapping and Outline of brain mapping

Neuroscientists, along with researchers from allied disciplines, study how the human brain works. Such research has expanded considerably in recent decades. The "Decade of the Brain", an initiative of the United States Government in the 1990s, is considered to have marked much of this increase in research. It has been followed in 2013 by the BRAIN Initiative.

Information about the structure and function of the human brain comes from a variety of experimental methods. Most information about the cellular components of the brain and how they work comes from studies of animal subjects, using techniques described in the brain article. Some techniques, however, are used mainly in humans, and therefore are described here.

Structural and functional imaging

Main article: Neuroimaging

There are several methods for detecting brain activity changes using three-dimensional imaging of local changes in blood flow. The older methods are SPECTand PET, which depend on injection of radioactive tracers into the bloodstream. A newer method, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), has considerably better spatial resolution and involves no radioactivity.Using the most powerful magnets currently available, fMRI can localize brain activity changes to regions as small as one cubic millimeter. The downside is that the temporal resolution is poor: when brain activity increases, the blood flow response is delayed by 1–5 seconds and lasts for at least 10 seconds. Thus, fMRI is a very useful tool for learning which brain regions are involved in a given behavior, but gives little information about the temporal dynamics of their responses. A major advantage for fMRI is that, because it is non-invasive, it can readily be used on human subjects.

Another new non-invasive functional imaging method is functional near-infrared spectroscopy.

No comments:

Post a Comment